Mujica, Jorge

Jorge Luis Mujica

Born in Mexico City in 1982

Lives in Los Angeles, California

Education

M.F.A Painting and Print Making, Yale University, School of Art 2012

M.A. Visual andCritical Studies,The School of the Art Institute of Chicago

B.A. Political Science and B.A. Art History California State University, Bakersfield

Selected Exhibitions

“Yale M.F.A. Thesis Show,” Yale University, New Haven CT 2012

“M.F.A. 2012” Yale University, New Haven CT 2011

“?” Sterling Memorial Library, New Haven CT 2011

“Vivid Conversation” Solo Show, Fishbowl Galley, Chicago IL May 2010

“Palimpsest”, Solo Show, Pentagon Gallery, Chicago IL April 2010

“Transitions and Translations” Concertina Gallery, Chicago IL, April 2010

“Opportunity Store” Hyde Park, Chicago IL, April 2010

“going to work” Solo Show, Knock Knock Gallery, Chicago IL, October 2009

“Sense and Form” Student Show, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, August 2009

“Department Store” Student Show, Sullivan Gallery,The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Dec 2008

Thesis Exhibition, Student Show, California State University Bakersfield, June2008

“Subliminal Consumption” Solo Show, California State University Bakersfield, May 2008

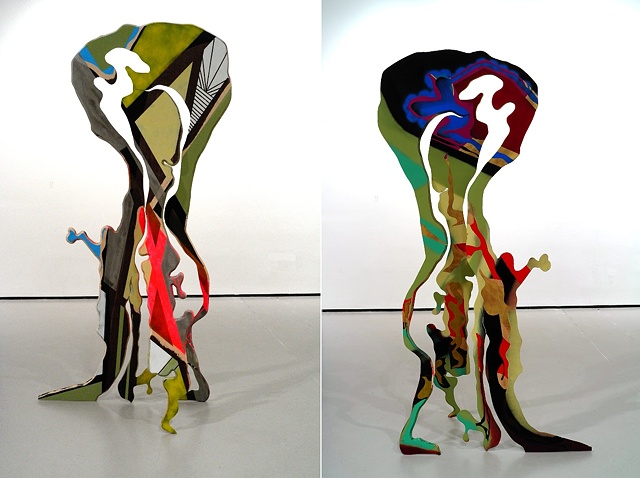

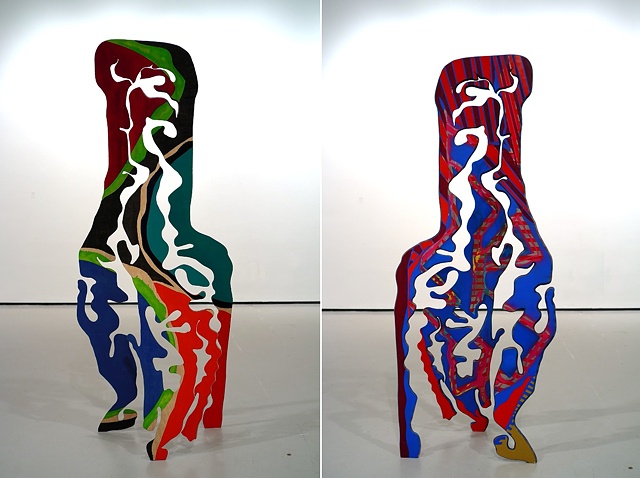

Jorge Mujica’s paintings, made from common plywood, commercial paints, and painted sand, are paintings of the Fotomat his family ran at the downtown corner of West Olympic and South Figueroa. They are paintings of the iconic beaches nearby, and they are paintings of the highways and avenues that are mapped and remapped by cars and

buses every day. But, for all of Jorge’s focus on the geography of L.A., his work is ultimately less interested in the city, per se, than it is in the dense set of experiences acquired living in it. Titles such as “Malibu Canyon Drive,” “Santa Monica Blue Bus No. 10,” “Bakersfield Bluff,” and “Take sunset past the 405 past Santa Monica past Highland past Western past Echo Park to Cesar Chavez” firmly anchor each piece within a particular and identifiable landscape, but the pieces themselves resist the fixity and interpretive comfort suggested by the clear references of the titles: they, in fact, must be understood by recourse to something much more subjective. Truly defining Los Angeles, Jorge suggests, requires passing the material reality of its concrete and sand through the filters of consciousness. This is what his abstract and expressionistic art captures, the irreducible what-it’s-like—or qualia—of growing up and living in a particular place. Once we see that he has used the opportunity of his thesis to tell the story about a very personal city, the central role that his two portraits play becomes legible: the “Portrait of Amanda,” his wife, and his own “Self Portrait.” They are as much a part of his Los Angeles as any of the locations or routes.

As personal as Jorge’s own story may be, though, the vibrant colors and geometry that make his paintings so striking are quintessentially Californian, opening them up as canvasses in which viewers can find their own experience just as easily as they can find his. Jorge’s paintings evoke the L.A. beach life and graffiti recognizable to anyone who grew up in the late 80s and the 90s, but they also recall something less visible than these more typical Hollywood elements: the aesthetic he knows all too well from L.A.’s Mexican culture. Perhaps more than anything else, Jorge’s paintings push the boundaries of what the city is and who is allowed to define it.

One piece, however, qualifies Jorge’s otherwise Utopian tone. In “Pete Wilson / Daryl Gates,” arguably the most visually complex of the paintings, Jorge forces himself and his viewers to reconsider what his general optimism really represents. What happens to our sense of his art—and the city—when we are confronted with the Rodney King beating and Proposition 187? Ultimately, Jorge leaves this question unanswered: Los Angeles, the sum of its history and cultures, remains as both the thread that ties his paintings together and the one that threatens to pull them apart. Like the pieces themselves, often freestanding and always without fasteners, Jorge’s Los Angeles refuses to be wrapped up, easily defined. He cannot settle on what the city is, and insists that we shouldn’t either.

Aaron Pratt